Journal of Political Risk, Vol. 1, No. 1, May 2013.

Brazil has been the hot investment ticket internati

onally for six to eight years. The common wisdom is that it has outgrown its “country of the future” label and has become a country of the post-2008 financial crisis. Investors now expect Brazil to grow into a first-world economy. Not so fast. While annual growth between 2005 and 2010 was consistently above 5%, it has stagnated since mid-2011. In 2012, its GDP grew a paltry 0.9% — the weakest of the five BRICS countries. It is time to take a cold look at whether the political factors promoting growth in Brazil between 2005 and 2010 are still operational.

Inflation

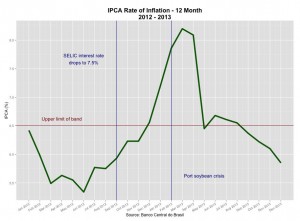

Coupled with anemic growth, the monster of inflation that devoured Brazilian economic performance in the 1980’s has again emerged as the government has had difficulties controlling the consequences of that period of sustained high growth. Brazil sets a target range for inflation. Since 2006, this range has been between 2.5% and 6.5%. In 2011, inflation exceeded its limit for three months and it has been doing it again since early 2013.

Part of the problem is a pattern of denial by the Minister of Finance, Guido Mantega. After six years in office (four under President Lula da Silva and two more under current President Dilma Rousseff), he has continually said either that inflation is not too high, that it’s already on the decline, or that it’s some external force’s fault. Foreign investors have lost confidence in Mantega’s pronouncements and his ever-changing fiscal policy moves that leave private industry confused about what the government wants.

Even popular government decisions have had an inflationary side effect. As of September 2012, the government lowered its prime interest rate, the SELIC rate, below 8% for the first time. Given a short lag for the rates to pass down from the Banco Central to consumer interest rates, the reduction of rates had the desired expansionary effect by the Christmas buying season, but as the graph shows, it fueled the late-2012 surge in inflation.

Taxes

Contributing to economic pressures is the increase in effective taxation rates, which has reached the 48% level — an increase of 12% over the ten years that Lula and Dilma have been in office. One of President Rousseff’s persistent claims is that she has reduced taxes for businesses. Indeed, she and Mantega have reduced taxes, but only for favored industries, such as automobile and white goods manufacturing. These industries, which have had a significant excise tax removed, have in turn reduced the price of most automobiles. But other industry sectors and individuals must pay more in taxes to compensate for loss in tax revenue. Overall, taxes revenues have increased dramatically, even at a time when economic growth is barely positive.

On the positive side, the Labor Party (PT) government has significantly increased the size of the middle class and reduced poverty over the last 10 years. Employment is at a record high (the unemployment rate sits at a record low of 5.3%) and many people who have spent their lives in Brazilian slums (favelas) are now able to buy homes financed by government-owned banks. Many of these recently emerged middle-class Brazilians are now also buying new cars, and benefitting from the tax reductions for the automobile industry.

Infrastructure

This brings us to Brazil’s major problem: infrastructure. This year, Brazil’s agricultural industry had a record harvest, particularly of soybeans, its fourth straight record year. However, many overseas buyers canceled orders because the ports are in such disarray that the trucks bringing the soy to the ships simply could not unload fast enough. Kilometers-long backups of vehicles clogged highways near Brazil’s major ports for weeks. The airports are suffering from a similar lack of investment, despite the concessions to private operation that the airport agency provided for a few major airports (especially São Paulo’s Cumbica International Airport in Guarulhos). Most highways in Brazil also remain dangerous, and the railway system is being redeveloped at a glacial pace. Just this week, the government announced that the Transnordestina railroad it is building will be delayed another two years (to 2015) and will cost approximately double its original 2007 estimate.

Beyond transportation, it is also not at all clear that the government has provided for sufficient new hydroelectric capacity to keep Brazil from suffering power blackouts in 2016. It has focused its major power development effort on the Belo Monte project that suffers from considerable environmental opposition and constant labor strife. It will be the second largest hydro project in Brazil upon completion. Despite the emphasis on grandiose projects, the problems facing the Brazilian power industry are more mundane. Two recent blackouts in the federal capital Brasilia were blamed on transient technical failures, but outside experts blamed the lack of capacity and poor maintenance on the regional transmission system around the capital.

Adding significant pressure to the infrastructure problems are the country’s commitment to the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. Both events require new stadia in the Brazilian regional capitals and transportation, hotel and other tourist investments. Neither the federal nor the state governments handle these particularly efficiently. The country’s most important stadium, Maracanã in Rio de Janeiro, will reopen in the first week of June for an international friendly soccer match against England, but will need every day possible from then until the World Cup begins to complete the project. The World Cup and the Olympics are also draining money from other infrastructure areas, which arguably are more important to the country’s long-term economic health. How this equilibrium among infrastructure needs will be maintained is one of the key questions governing growth over the next two years.

It is impossible to provide a summary of the Brazilian economy without mentioning both crime and education. The public schools consistently rank among the lowest in the world despite Brazil’s major steps forward in reducing income inequality. And, Brazilians, like many citizens of developing countries, have much to fear in terms of persistent street crime that seems immune from law enforcement.

Thus, Brazil does have a new, well-employed middle class. These are the people who can make the economy grow. However, its continuing infrastructure bottlenecks, the government’s focus on grandiose projects, and poor prioritization of economic programs severely constrain growth in the country in comparison to its BRICS counterparts. Investors are right to be cautious.

What should Brazil do to improve its situation? In the best of all possible worlds, where governments humbly admit to impetuosity and error, the government would cancel the Olympics to devote the country’s resources to transportation and ports. However, that is not reality. At the very least, Brazil should cease its grandiosity after the Olympics and focus on domestic capital projects and education. Without these, the country will fall back into its past as a “country of the future.”

James R. Hunter is a consultant and Professor of Administration at BBS, Business School São Paulo and other institutions in São Paulo, Brazil.

Peer review status: (2/3)